On a whim, I visited a web auction site dealing in surplus government property.

I spotted two very old laptops, which claimed to be still operational,

and I placed a bid of $40.

A few days later, I received an email saying I was the proud owner of two

HP Omni Book XE3 loaded with a Celeron1 32bit processor!

On a whim, I visited a web auction site dealing in surplus government property.

I spotted two very old laptops, which claimed to be still operational,

and I placed a bid of $40.

A few days later, I received an email saying I was the proud owner of two

HP Omni Book XE3 loaded with a Celeron1 32bit processor!

By todays standards, the HP Omni Book XE3 isn't exactly a race horse with its 1066 MHz clock, 128M of RAM running at 100 MHz, and 10/100 Ethernet LAN communications. These laptops2 date back to 2000, the early days of the Internet, and are unashamedly equipped with a built in phone jack / modem, PCMCIA card slots, a 1.44-MB floppy disk drive, and proudly hosting Microsoft Windows 98 Second Edition!

The installed 10G drive was wiped clean but the laptops did come with the ordinal recovery disk. Using the recovery disk, I quickly got the Microsoft Windows 98 operating system installed. There was no login prompt or password required ... wow, not much security here.

I activated the browser, that being Microsoft Internet Explorer 6.0. During the activation, it asked if I wished to access the Internet via a modem ... Ahhhh, nooo! It's the ghost of Internet past! Initially, this old browser only partly worked. I then set it to accept all cookies and it behave much better and was usable, but it would hang sometime and it wasn't at all pretty.

With the browser and the slow Internet connection, I figured that I could then down load the Linux distribution that I needed, and boot it from the disk. My plan is to get a light-weight Linux distro installed and use it as X Server with my desktop Linux system as its X Client, that is, turn the laptop into a X Terminal3. I was hoping to use Lubuntu as my Linux distro. This alternate version of Ubuntu is for computers with less than 700 MB of RAM, so I'm hoping it will do the job.

What I shortly discovered is that the antique hardware and OS (Microsoft Windows 98) got in the way. All the method I tried to install Lubuntu ran into walls. First, the ISO image was to large to burn to a CD-ROM, it required a DVD, but this old laptop isn't DVD equipped. Booting the ISO from a USB thumb drive wasn't possible with the old laptop BIOS. When I attempted to load the ISO image from the hard disk using methods found at Downloading Lubuntu 13.10, Installing Lubuntu, and Installation/FromWindows, I found that these tools and methods wouldn't work within Windows 98.

Testing Light-Weight Linux Distributions

I concluded that it would be best to burn the Linux distro onto a CD-ROM using my current desktop computer and boot the laptop with the CD-ROM as a live system. It was still my desire is to use Lubuntu, but give the limitations of this laptop, I'll also try out Damn Small Linux (DSL), Puppy Linux, and Tiny Core Linux (other options can be found here).

Damn Small Linux (DSL)

For my first trial, I choose to install Damn Small Linux (DSL). DSL (based on the Debian distro)4 was released in 2003 to specifically create a Linux operating system for older hardware. DSL supports older machines with minimal memory by disabling all unnecessary daemons or services. DSL gives you a tool to individually load and manage daemons, and you can load bundled applications designed with stingy resource use. DSL was designed, tested, and runs on old computers by retains support for many old devices.

The installation of DSL on the laptop happened without any difficulties. I followed the excellent instructions give in the article How to Download and Install DSL Linux. Every thing came up nicely.

But there are problems. A major short coming of this distro is that DSL development seemed to be at a standstill for a long time. This, and the fact that I can't find much documentation on how to support WiFi with DSL, gives me major concerns about using it. Never the less, the good news is that I now know I can get some version of Linux operational on this old laptop.

Lubuntu

My next test install was Lubuntu. The article "Lubuntu: Finally, a Lightweight Ubuntu" claims that Lubuntu has snappy responsiveness on older computers. This seems to be dependent on having a Pentium III processor and 128M or more of memory. This laptop seems to just meet this criteria and so I pushed forward.

I down loaded the Alternate version of Lubuntu from the site Lubuntu Alternate ISOs for low-RAM PCs, created the CD-ROM, and booted the laptop with the CD-ROM. The install started smoothly but slowed down and took several hours ... bad sign. Once installed, it hung during boot up. Looks like Lubuntu is out of the running. It appears the 128M of RAM is just too small for Lubuntu.

Puppy Linux

Puppy Linux is a popular light-weight Linux distro. I successfully installed Puppy Linux, but once installed, it performed badly when I fired up applications like a browser. A closer reading of the Puppy Linux documentation informed me that the Linux Kernel is going to require 100M of RAM. So any reasonable size application will cause performance problems.

Tiny Core Linux (TCL)

My final attempt was Tiny Core Linux (TCL), which comes in three ISO images,

include CorePlus which is the installation image I required.

I download the CorePlus, image, burned it to a CD-ROM, booted it,

and selected "Boot Core with X/GUI (TineCore) + Installation Extentions" from the boot menu.

This will enable you to perform a hard drive install of TCL.

See the Tiny Core Linux installation documentation for procedures.

(You can also do a manual install,

with a reformating of the disk, if you boot directory is screwed up form previous installs.)

TCL install without a hitch and ran very nicely. It has a very smaller RAM footprint like DSL but is actively supported, well documented, including a book call Into the Core: A look at Tiny Core Linux. Given all this, TCL seems like a good choose for my X Terminal plans.

Getting to Know Your X Environment

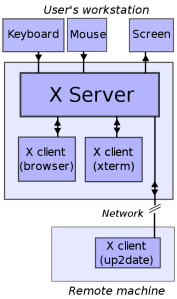

As stated earlier, my objective is to use the TCL laptop as a

X Terminal with my desktop Linux as the remote system.

To do this successfully, you need to understand the X Window System as it will operate

on the X Terminal and the remote system.

The beauty of X is the flexibility it gives you in creating a graphics applications

and distribute them across a network.

On the other hand, this flexibility creates its own complexity

and makes it challenging to understand how X operates.

As stated earlier, my objective is to use the TCL laptop as a

X Terminal with my desktop Linux as the remote system.

To do this successfully, you need to understand the X Window System as it will operate

on the X Terminal and the remote system.

The beauty of X is the flexibility it gives you in creating a graphics applications

and distribute them across a network.

On the other hand, this flexibility creates its own complexity

and makes it challenging to understand how X operates.

To clarify this, a typical X Window System consists of the following components:

- X Window System (aka X, X11, X-Windows) - X Window System provides the basic framework, primitives, and protocals for a graphical user interface (GUI) environment. X does not mandate the user interface — this is handled by individual programs. As such, the visual styling of X-based environments varies greatly; different programs may present radically different interfaces. There are several implementation of X, including X.Org, XFree86, Cygwin/X, and many more.

- X Server (aka X Display Server) - This creates the graphical environment on a graphical display device using the X Display Protocol. An X Server program runs on a computer with a graphical display and communicates with various X client programs, along with peripherals like the keyboard and mice. Examples of X servers are Xming and XServer.

- X Client (aka X Application) - An X client is an application program that displays on an X Server but which is otherwise independent of that server. X Clients are built using software libraries that support the X Window System framework.

- X Window Manager - The Window Manager perfroms the tasks of managing how you interact with your application windows. Window Manager's are often designed to be highly customizable via configuration files. The Window Manager takes care of deciding the position of windows, placing the decorative border around them, handling icons, handling mouse clicks outside windows (on the “background”), handling certain keystrokes, etc. Examples are WindowMaker, sawfish, and fvwm.

- X Session Manager - The session Manager automatically starts a set of applications, setting up, and restoring a working desktop environment. More precisely, it is the set of applications managing these windows and the information that allow these applications to restore the condition of their managed windows if required. The X session manager saves and restores the state of sessions.

- X Display Manager (aka Login Manager) - This program shows the graphical login prompt in the X Window System. This is the first X program run by the system if the system (not the user) is starting X and allows you to log on to the local system, or network systems. More generally, a Display Manager runs one or more X Servers on the local computer and accepts incoming connections from X Servers running on remote computers. The local servers are started by the Display Manager, which then connects to them to present the user the login screen.

- Desktop Environment - A desktop environment such as LXDE, XFCE, KDE, GNOME, or Ubuntu's Unity are a suite of applications, fonts, icons, configuration files, and design patterns used to integrate all the above X Window System components to provide a consistent user experience. Display Environments typically provide a handful of applications bundled together to accomplish tasks in a graphical manner as opposed to using the command line. They often come with a desktop shell, which is a place to hold your fancy shortcut icons, as well as other tools such as file managers.

Given all this, starting an X session is typically done in one of two ways:

- The X session is started via a X Display Manager, which provides the user login prompts on a GUI screen. In this case, the Xorg process is started at boot time along with the X Display Manager.

- If Xorg wasn't started at boot time, the user starts X manually after logging in to a text console. This is typically done with the

startxcommand, which is a simple shell script wrapper forxinit.

In either case, X runs with root privileges since it needs raw access to hardware devices.

In the X Window System,

the X Display Manager runs as a program that allows the starting of a session

on an X Server from the same or another computer.

A Display Manager presents the user with a login screen which prompts for a username and password.

A session starts when the user successfully enters a valid combination of username and password.

The X Display Manager function was established, in part, to support standalone X Terminals.

A Display Manager can run on the local computer where the user sits or on a remote one. When local, the Display Manager starts one or more X Servers, displaying the login screen. When the Display Manager is remote, the Display Manager works according to the X Display Manager Control Protocol (XDMCP)5.

The XDMCP protocol mandates that the X Server starts autonomously and connects to the Display Manager. You configure an XDMCP Chooser program running on the local computer (or X Terminal) to connect to a specific remote X Display Manager or to display a list of suitable hosts (if configured to do so) that the user can choose from. When the user selects a host from the list, the XDMCP Chooser running on the local machine will send a message to the selected remote computer's Display Manager and instruct it to connect the X Server on the local computer or terminal.

Note that unlike vncviewer, which just duplicates a hosts current screen on a remote system, XDMCP allows several different users to login and run different X sessions at the same time. Your not sharing a desktop screen image, your starting seperate X Window session on the remote machine.

If your Linux box boots into a graphical login screen, like my Ubuntu desktop system,

you are already running a Display Manager.

Specifically, my desktop Linux box is using lightdm as its X Display Manager.

You can determine this by running cat /etc/X11/default-display-manager

or ps -A | grep dm.

On the other hand, when I install TCL on the vintage laptop, you see no graphical login screen.

So you know that TCL isn't using a X Display Manager.

For my desktop Linux environment, I'm using Ubuntu's default environment. That is the Unity Lightweight X11 Desktop Environment (LXDE). It consists of:

- Window Manager - Openbox, the default window manager of LXDE

- Display Manager - LXDM is the Display Manager for LXDE

- Session Manager - LXSession is the standard session manager used by LXDE and it's desktop-independent and can be used with any Window Manager.

What is happening when you start up Unity on the desktop system and run X? The following is an abbreviated summary of startup activites.

- The kernel starts the

initprocess as process number 1, and it is responsible for starting all other processes. initstarts the LXDE Display Manager/usr/sbin/lightdmfairly late in the init process (the system dbus, filesystem and the graphics display system all must be ready).lightdmcreates an xauthority file and then starts X, starting it on virtual terminal 7- The

unity-greeterget's the names of potential Window Managers, and in my case that would beubnutuand so it uses/usr/share/xsessions/ubuntu.desktop. - Once logged in, the files from

/usr/share/xsessions/ubunutu.desktopnow determine the rest of the startup sequence. - The

/usr/sbin/lightdm-sessionshell script is run with the argumentsgnome-session --session=ubuntu /usr/sbin/lightdm-sessionthen runs$HOME/.profile, loads$HOME/.Xresources,$HOME/.Xmodmap, runs scripts in/etc/X11/xinit/xinitrc.d, runs the Xsession scripts in/etc/X11/Xsession.d/*, using the options in/etc/X11/Xsession.options.lightdm-sessionstarts a Window Manager, or for Unity, starts thegnome-sessionSession Manager. The Window Manager uses the Unity/usr/share/xsessions/ubuntu.desktopconfiguration file.gnome-sessionstarts the specified program from/usr/share/gnome-session/sessions/and starts applications from~/.config/autostart/and/etc/xdg/autostart.

So now you have some small insight into what the X Window System is doing, but what are the important things one should take away from all this?

- The remote, that is my Linux desktop system, must use a Display Manager and it needs to be configured to accept logins from network terminals. This means configuration files must be set to accept the login request and the XDMCP protocol must be operational. That is, configuring X Display Manager as an XDMCP Server.

- The X Server on the local system, that is the vintage PC, must be configured to use the XDMCP protocol, be directed to log into the remote system, and not establish its own local desktop environment. That is, configuring X Server as an XDMCP Client.

As to the mechanics of making this happen, the following articles do a good job of explaining what needs to be done (and I'll provide the detail steps later):

What is My Window Manager

You can configure Ubuntu to run different Window Managers within any given Desktop Environment. This makes it a bit of a challenge in knowing what window manager your using. Detecting which Window Manager your using require you to sort of know what to look for.

# detect the window manager you are using ps -ef | egrep "xfwm|twm|metacity|beryl|compiz" | grep -v egrep

What is the Display Manager being used? The Display Manager runs before you log in, and as such, it's by the system is configured. On a Ubuntu system, you can find the Display Manager being used via

# print our the Display Manager being used

cat /etc/X11/default-display-manager

Compositing Window Manager Compiz

Compositing Window Managers process the on-screen rendering of application windows by using a special off-screen buffer to handle sweet effects and eye candy. Basically, you can stack your application windows with added effects like drop shadows, transparencies, and 2D / 3D animated effects. The Window Manager composites the window buffers into an image representing the screen and writes the result into the display memory. The Ubuntu default Window Manger, Compiz, is just such a solution. In fact, the Unity interface, is written as a plugin for Compiz.

As I experimented with TCL running as a X Terminal and my Linux desktop as my Display Manager connected via XDMCP, but I had significant Window Manager problems. Basically, it would not start when I logged in. I discovered this via this script:

# detect the window manager you are using ps -ef | egrep "xfwm|twm|metacity|beryl|compiz|fluxbox" | grep -v egrep

Given the age of this vintage laptop (around year 2000) and the fact that Compiz's inital release was in 2006, I concluding that Compiz would never run on this hardware. Time to try another Window Manager.

X Window Remote Application

There are a few ways to run X windows applications remotely

(i.e. running an X Windows application on a remote computer and having the graphical part show up on your local computer).

For something quick, use the SSH method in an xterm window:

ssh -X login@remote-computer

This will give a terminal session within the xterm window on the remote computer.

The -X switch says to export graphics from the remote computer (remote-computer)

to the computer you at actually sitting on (i.e. the local-computer).

For many uses, this works fine, but it doesn't give you the full login experience on the remote computer.

Specifically, the desktop is still the local computer,

so picking any desktop icon or menu will result in a local X client.

This isn't what I want ... I want access to the remote desktop.

To do this, you could leverage the Linux Terminal Server Project (LTSP) Sterminal, or even consider Virtual Network Computing (VNC), but these have too heavy a memory footprint for the vintage laptop I'm using. And in the case of VNC, your really sharing an existing screen, not creating a new session. I'll need to use the less secure classical method of using XDMCP. Basically, on the remote computer (remote-computer) I need to be running a special daemon that answers requests to login from a X Server. To establish this, I'll need to do the following:

- On the remote computer - Configure the Display Manager to accept logins from a remote X Server

- On the local computer - Configure the local Display Manager to use the remote Display Manager. This amounts to configuring the Display Manager to run "XDMCP Chooser". An alternative is to establish a X session and then log into the remote via

Xnest. Xnest can be used to locally display the desktop of a remote computer.

Getting to Know Ubuntu Unity

Unity is the Desktop Environment that is shipped as the default Ubuntu installation,

and claims it's focus is on simplicity and consistency across multiple devices

(e.g. across TV, mobile, tablet, and desktop).

Several years ago, Ubuntu moved from GNOME to Unity, never the less,

the Unity interface should run all GNOME-based applications without modification.

I guess that is why Unity is often introduced as a desktop shell for GNOME.

This is not the same as a totally new desktop environment.

A desktop shell is the interface that you use.

Unity will still use the same GNOME apps and libraries that the any GNOME desktop does.

In this way, GNOME can be thought as an example of another shell for GNOME.

The debate concerning GNOME vs Unity inciting a lot of reactions from users.

Unity is the Desktop Environment that is shipped as the default Ubuntu installation,

and claims it's focus is on simplicity and consistency across multiple devices

(e.g. across TV, mobile, tablet, and desktop).

Several years ago, Ubuntu moved from GNOME to Unity, never the less,

the Unity interface should run all GNOME-based applications without modification.

I guess that is why Unity is often introduced as a desktop shell for GNOME.

This is not the same as a totally new desktop environment.

A desktop shell is the interface that you use.

Unity will still use the same GNOME apps and libraries that the any GNOME desktop does.

In this way, GNOME can be thought as an example of another shell for GNOME.

The debate concerning GNOME vs Unity inciting a lot of reactions from users.

Although Unity is a single graphical experience, you can think of it in three broad buckets:

- Design – the visual design and interaction experience

- Platform – the core Unity platform software

- Services – a set of functions that Unity makes available to applications for integration and for content to be viewed.

The Unity user interface consists of several components:

- Top Menu Bar – is a global application menus not located in the application’s windows, they’re located on the top menu bar. You see the application’s menu when you mouse over the top of a window.

- Launcher – is at the left side of the screen is where you’ll launch frequently used applications and switch between running applications.

- Dash – an overlay that allows the user to search quickly for information both locally (installed applications, recent files, bookmarks, etc.) and remotely (Twitter, Google Docs, etc.) and displays previews of results. Open the Dash by clicking the Ubuntu icon at the top left corner of the screen. You can also press the Super key to open the launcher (the Super key is also known as the Windows key).

- Quicklist – the accessible menu of launcher items

- Head-Up Display (HUD) – allows hotkey searching for top menu bar items from the keyboard, without the need for using the mouse, by pressing and releasing the Alt key.

- Indicators – a notification area containing displays for the clock, network and battery status, sound volume, etc.

# Just notes # make sure the last entry of the .xsessionrc file is run in the background # to restart Unity setsid unity # or should you use setsid unity --replace # to logout via the terminal gnome-session-quit # restart X without rebooting /etc/init.d/gdm restart # kill your graphical interface using sudo service lightdm restart # restart your session manager # see this http://manpages.ubuntu.com/manpages/lucid/en/man1/gnome-wm.1.html

Like many desktop envirnments, Ubuntu Unity can change its look & feel by changing the themes.

These alternative theme files are extracted to ~/.themes or /user/share/themes directores.

Once a theme is established, it can udergo additional tuning via the

Unity Tweak Tool, which is a settings manager for the Unity desktop.

This configuration tool provides users access to features and configuration options,

and brings them all together in a polished & easy-to-use interface.

To install this tool, use

sudo apt-get install unity-tweak-tool

The most transparent and precise way to configure the Unity envirnment is to modify the file

/etc/lightdm/lightdm.conf.

The post "Understanding lightdm.conf" is a good read to better understand lightdm.conf

but keep in mind that some utilities it suggest are no more.

As of Ubuntu Trusy 14.04,

the command line utility lightdm-set-defaults is no longer available.

This is because lightdm now using a configuration directory /etc/lightdm/lightdm.conf.d/

rather than a single configuration file.

The files in this directory can be edited by hand, new files can be added, or files can be removed.

There is no manpage for lighdm.conf, but there is an example that lists all the options

and a bit about what they do, just look in /usr/share/doc/lightdm/lightdm.conf.gz

(If you use vim, you can just edit the file and it will be automagically ungzipped for you).

While there are many things you can set within lightdm.conf,

running a command When X starts, when the greeter starts, or when the user session starts

may be the more useful for our purposes.

For example, when lightdm starts X you can run a command or script, like xset perhaps.

display-setup-script=[script|command]

You can do something similar when the greeter starts:

greeter-setup-script=[script|command]

or when the user session starts:

session-setup-script=[script|command]

A potentially even more granular way to configure the Unity envirnment is via

minimpulating the GSettings classes, which is a API for application settings.

To support this, there is gsettings which offers a simple command line interface to GSettings.

GSettings is a GLib implementation of the DConf spec, which stores its data in a binary database.

The gsettings command line tool is simply a tool to access or modify settings via the GSettings API.

Applications using GSettings/DConf install allication configuration data or schemas.

A schema is basically is a list of the available settings for that application.

There are two types of schemas, standard and relocatable schemas.

Important to understand that for relocatable schemas we need to provide a

path on top of the normal schema name like org.gnome.login-screen.

An application does not need to know where or how the data is stored,

just how to access that data and recieve a notification if and when the data changes.

To list all the available schemas6, enter

gsettings list-schemas

Now that we have a list of the schemas we can look at what keys they provide.

Keys are the actual settings we manipulate.

We can list them with gsettings list-keys <schema name>.

For example,

gsettings list-keys org.gnome.login-screen

You can also list both the keys and their current values by running gsettings list-recursively <schema>.

For example,

gsettings list-recursively org.gnome.login-screen

As mentioned before relocatable schemas need an aditional path before we can list and manipulate the keys. Other than the path we treat the the two types of schemas the same way from the command line. The location of the relocatable schemas are within the path and not in the default location. For example we added a colon followed by the path:

gsettings list-recursively org.gnome.login-screen:/org/mate/panel/objects/object_0/

You'll find other uses for gsettings on its manual page.

For example,

Unity desktop comes with overlay scrollbars enabled by default.

You can disable overlay scroll-bars, if you don't like them.

Enter the following command in a terminal to disable overlay scrollbar:

gsettings set com.canonical.desktop.interface scrollbar-mode normal

If you want to get back overlay bars, enter following command:

gsettings reset com.canonical.desktop.interface scrollbar-mode

With all these oppertunities to reconfigure Unity, the possibilities of screwing thing up are very high. In case some settings are messed up and you want to reset Unity and Compiz to their default settings, the standard way is to use

# Careful ... this will reset all Unity & Compiz to their default options

unity-reset

To restart Unity after running the above command (or restart it any time), use the command

setsid unity

You can find more examples of configuring Unity via gsettings and other tools in the postings:

- Tweaks/Things to do after install of Ubuntu 13.10 Saucy Salamander

- Things/Tweaks To Do After Install Of Ubuntu 14.04 Trusty Tahr

Getting to Know the TCL Operating System

![]() As stated earlier, it appears that Tiny Core Linux (TCL) will be my best choose

for this vintage laptop conversion into a X Terminal.

Like Damn Small Linux, Tiny Core Linux (TCL) is a minimal Linux operating system

initially using BusyBox as its core system,

but latter replace with GNU's Coreutils.

Tiny Core is exactly what the name suggests,

a tiny core of an operating system which boots to a fully functional graphics desktop

called Fast Light Toolkit (FLTK), pronounced "fulltick",

which includes the Fast Light Window Manager (flwm).

As stated earlier, it appears that Tiny Core Linux (TCL) will be my best choose

for this vintage laptop conversion into a X Terminal.

Like Damn Small Linux, Tiny Core Linux (TCL) is a minimal Linux operating system

initially using BusyBox as its core system,

but latter replace with GNU's Coreutils.

Tiny Core is exactly what the name suggests,

a tiny core of an operating system which boots to a fully functional graphics desktop

called Fast Light Toolkit (FLTK), pronounced "fulltick",

which includes the Fast Light Window Manager (flwm).

Tiny core can be run on new, high performance computers. It can also be run on older, slower computers. Minimum performance requirements depend on which programs you install in Tiny Core. Most programs will run on a computer with 256 mb of ram. Tiny core can be run on a computer with 128 mb of ram, with selected programs. It may not be worthwhile for most people to run Tiny Core on a computer with less than 128 mb of ram, as even less programs will run. The absolute minimum to run Tiny Core is 48 mb of ram.

Tiny Core is designed to run entirely from a RAM copy created at boot time. While you can do a traditional hard drvie install, Tiny Core is designed to run from a RAM copy created at boot time. Besides being fast, this protects system files from changes and ensures a pristine system on every reboot. Easy, fast, and simple renew-ability and stability is a principle goal of Tiny Core. The core system provides most of what you need for a working environment, which they can then tweak from there via loadable applications.

Frugal is the typical installation method for Tiny Core. That is, it is not a traditional hard drive installation, which we call "scatter mode", because all the files of the system are scattered all about the disk. With frugal, you basically have the system in two files, vmlinuz and core.gz, whose location is specified by the boot loader. Therefore, the TCL Live CD ISO image consists of four components:

- Bootloader (

/boot/extlinux) - Linux Kernel (

/boot/vmlinuz) - Core initrd (

/boot/core.gz) - Extensions (

/tce/onboot.lst,/tce/optional)

The default bootloader used by TCL is extlinux but others can be installed (such as grub).

You find extlinux's configuration file in /mnt/sda1/tce/boot/extlinux/extlinux.conf.

Tiny Core consists of a small kernel and initial RAM disk,

which ultimately boots into a basic FLTK graphical environment.

The computer’s hardware is configured on boot and should mostly work out of the box.

TCL is RAM based - the "core" utilities are packed into the core.gz file

which is then unpacked into RAM when the system boots and forms our primary filing system.

After that TCL searches any attached storage for the directory tce.

This directory holds optional extensions to the operating system such as the graphical desktop

and anything else we care to add.

The extension files are actually compressed filing systems,

read-only tgz files,

and Tiny Core mounts these individually under /tmp/tcloop/<application_name>

and then merges them with the main filing system.

Given that applications are load freash on each boot,

how do we handle application's configuration file that need to be preserved?

This is where Tiny Core's user editable /opt/.filetool.lst file comes into play.

This contains a list of all (potentially changed) RAM-based files

or directories that we want to persist across reboots (which logically has to include itself).

Tiny Core handles this with the filetool.sh script.

When run with the -b option this packages up all these files into a single compressed file (mydata.tgz)

that it saves in the tce directory.

When the script is run with the -r option it does the reverse and restores the saved files.

The restore happens automatically as the system boots.

By default the /opt/filetool.lst file includes the /home and /opt directories.

Remove this entries if you wish (e.g. when backup take a long time).

NOTE: You can do backups from GUI or on command line via

filetool.sh -b. This will backup files to the/etc/sysconfig/tcedir/mydata.tcz. This way, a poweroff or reboot will not undo your work.

Many options, such as a choice of either an ALSA or OSS sound server, are left up to the user. Once inside the environment, the user is then able to connect to the online repositories in order to install the applications they desire and configure their system. TCL has a very simple package manager that provides a list of available packages to install. The user need only select a package and the manager will download it with all required dependencies and install them to the system.

TLC's package manager, the Apps tool, has several methods of installing applications

Tiny Core uses the Apps tool to place application extensions in the

tce/ directory and to flag them as either "OnBoot" (mount at boot)

or "On Demand" (do not mount at boot, but create a special menu

section for easy access and display an icon if available).

(For my purposes of creating a X Terminal, I see no for any of these options other than OnBoot).

- OnBoot - This is the default method. This extension will be installed, and added to the onboot list, to be mounted on the following boots.

- OnDemand - A loading script will be generated for this extension. Instead of being loaded on boot, the icon/menu entry for this extension will load the extension when you first need it. This option speeds up your boot time, at the cost of making the first start of the application slower.

- Download + Load - The extension will be downloaded and installed for this session only. It will reside within the directory sytem, but since it is not added to the onboot list, it will not be loaded after a reboot.

- Download Only - The extension will only be downloaded, nothing more will be done.

In the default configuration of TCL, anything written to /opt and /home

directory trees will be written to the hard disk and so are persistent.

Any files created elsewhere are volatile and need to be added to the file /opt/.filetool.lst

if we want them to persist across reboots.

Tiny Core doesn’t actually install anything onto the system in a traditional way. Instead it stores the binary packages in memory which are then laid over the top of the existing system. These packages are actually called extensions and when the system boots each and every time it will load these extensions from a location you specify.

Tiny Core provides two different types of extensions: TCE and TCZ. The former is a compressed tarball which is extracted into RAM over the booted system environment. The disadvantage of this method is that it uses up more RAM the more programs you have installed. The latter is more efficient as it actually loop mounts the packages onto the system, rather than extracting them into RAM. This means that they are only loaded into memory when you actually use them, similar to that of a more traditional install where they sit on a hard drive. If you’re going to have many applications installed, this is the better option.

TCL has the ability to save your data and restore it on boot.

You can also change system files and on boot these will also be restored,

just after the extensions are loaded.

So if you do want to customise a package, you can do so and have it stay that way each time you boot.

The system also takes mount point arguments at boot time,

so users can specify a partition to use as their /home directory, for instance.

To investigate futher on the interworkings of TCL, the article "Tiny Core: The Little Distro That Could" gives a good, quick introduction to Tiny Core, and this video provides an excellent introduction to Tiny Core Linux File Architecture and Boot Process. The Thin Client website has a section on Tiny Core Linux. And of course, if your really ambitious, you can read the book "Into the Core: A look at Tiny Core Linux".

Getting to Know Your Network Security Options

As stated earlier, the XDMCP protocol used to support the X Terminal isn't encrypted7.

So using the X Terminal outside of ones secure LAN or WAN, say across the internet, is risky business.

Any passwords or credit cards will be passed as plan text.

But in my case, I'll be using this only on my home network.

So the key here is making sure you have good firewall protection on your router and

strong encryption on you wireless network.

I'm using a router supplied by my internet provider,

and by default, its configured for old encryption standards and not the more secure WPA2.

As stated earlier, the XDMCP protocol used to support the X Terminal isn't encrypted7.

So using the X Terminal outside of ones secure LAN or WAN, say across the internet, is risky business.

Any passwords or credit cards will be passed as plan text.

But in my case, I'll be using this only on my home network.

So the key here is making sure you have good firewall protection on your router and

strong encryption on you wireless network.

I'm using a router supplied by my internet provider,

and by default, its configured for old encryption standards and not the more secure WPA2.

I have to admit that, up until this project, I haven't been thinking much about the latest WAN encryption recommendations. My concern was, amid the alphabet soup of what security standards, how do you merge support for a mix of client devices that support the range of WiFi security protocols? The solution was to get myself the strongest available security by using a wireless access point (AP) equipment that supports all the 802.11i-standards: Wired Equivalent Privacy (WEP), Wireless Protected Access (WPA), and Wireless Protected Access-2 (WPA2). Like many people, I have some devices that don’t yet support WPA2 or WPA and, at best, might support WEP. WPA2, the strongest security, is not backward-compatible with WPA or WEP, but you can support all three security mechanisms on a single physical Wi-Fi network. However, client devices must find a protocol match on the APs to which they associate. In other words, WEP has to talk to WEP; it can’t talk to WPA or WPA2.

In the end, I bit the bullet and converted my home WiFi to WPA2. I followed the proceedures outlined here: How to Change Verizon Fios Router from WEP to WPA2, Plus Other Security Adjustments.

Establishing the X Terminal Solution

To create the X Terminal solution, and therefore install the Tiny Core Linux (TCL), its good to have a firm undersatanding of TCL and how its differes from an typical Linux install. Reading the TCL book is a good idea and so is watching JoeNobody010101 (your going to love this guy) who provides a series of videos titled "How to install and configure TinyCore Linux".Installing Tiny Core Linux on Local Computer

Before starting the step-by-step installation procedures, here are some important things to know.

Mount Mode Install

This TCL install will be in Mount Mode.

This means applications are stored locally in a directory named tce on a persistent store,

e.g. a supported disk partition (ext2, ext3, ext4, vfat).

Applications are mounted on reboot when present in /mnt/sda1/tce/onboot.lst.

Persistent File Storage

Tiny Core also supports persistent/permanent file storage.

You will back-up at power down and restored at reboot the directories

or files listed in the file /opt/.filetool.lst.

By default, this file contains the /home and /opt directories.

The list may be changed manually (using vi or other text editor) to include other files or directories.

Also, you can do the exclusion of particular files by listing them in /opt/.xfiletool.lst.

You can also backup and restore of these files anytime by using the utility filetools.sh.

Specifically, files are backed up by filetool.sh -b to persistent disk.

Boot Time Processes

To start processes at boot time,

/opt/bootsync.sh is the file where you should list the shell script.

The boot process will waits for them to complete.

If you need network access later, this might be a good place to wait for the network to come up.

/opt/bootlocal.sh is the is the file for all items that don’t need to be waited for.

This may include loading some non-essential module

(ISA sound cards, for example), or starting some server.

Once /opt/bootsync.sh is complete (and while /opt/bootlocal.sh runs in the background)

init regains control.

As the boot is now complete from init point of view,

it launches a terminal configured to do an automatic login to root and runs a script.

Root’s login script is setup to do one of two things:

it passes the control up to our regular user, named tc by default.

The tc login script does nothing out of the ordinary.

If an X server is available, and a text-only boot was not requested, X is started.

TCL Install Steps

To do the install, you need to follow these steps:

-

Boot TCL Image from CD-ROM

- Go to the Tiny Core Linux (TCL) website and find the IOS image that includes CorePlus. I download the CorePlus, image, burned it to a CD-ROM booting it on the Laptop.

- Go to the Tiny Core Linux (TCL) website and find the IOS image that includes CorePlus. I download the CorePlus, image, burned it to a CD-ROM booting it on the Laptop.

-

Configure the TCL Image for Installation

- Put the CD-ROM in the Laptop's drive, connect it via Ethernet to the Internet, and turn on the power.

- When it boots up, selected “Boot Core with X/GUI (TineCore) + Installation Extensions” from the boot menu. This will automatically install the

TC_Installprogram for installing apps. - Select "Apps" icon on the bottom and install the following application packages to "OnBoot"

- cfdisk.tcz

- Now open a terminal and enter "cfdisk". This will be used to format and partition the hard drive. I created a

sda1bootable drive with 9500Mb and asda2swap drive with 555.94Mb. Write to the disk and quit. - Now run

TC_Install. Select Frugal, Whole Disk, Install boot loader, and high-lightsda. - Still in

TC_Install, click the next arrow at the bottom and then selectext4file format. - Still in

TC_Install, click the next arrow at the bottom and the boot options list will appear. You'll select from this list by writing what you want on entry line. Enter the following:tce=sda1 swapfile=sda2 restore=sda1 home=sda1 opt=sda1 local=sda1 vga=792 host=XT xvera=1024x768x32. (NOTE: These parameters are placed within the file/mnt/sda1/tce/boot/extlinux/extlinux.confif you wish to exit them later.) - Still in

TC_Install, click the next arrow at the bottom and select- Core and X/GUI Desktop

- WiFi Support

- Wireless Firmware

- Still in

TC_Install, click the next arrow at the bottom and select Proceed. The disk will now be formated, partitioned, and software loaded as specified.

-

Boot TCL Image from Hard Disk

- Now its time to reboot the system, making sure to remove the CD. To do this, go to a terminal window and execute these commands

umount /mnt/hdceject /dev/hdcreboot

- Now its time to reboot the system, making sure to remove the CD. To do this, go to a terminal window and execute these commands

-

Activate Filewall, File Manager, and Sound

- Once you booted up from the disk, click on Apps and install

- fluff.tcz

- iptables.tcz

- alsa.tcz

- Activate the firewall (now and on all subsequent reboots) and sound by running the following commands in a terminal

sudo /usr/local/sbin/basic-firewall- Using fluff file manager, open

/opt/bootlocal.shand place in it/usr/local/sbin/basic-firewall noprompt.

- Using fluff file manager, open

/opt/bootlocal.shand place in itopt/alasetc/modprobe.confusr/local/etc/asound.state

- To permanently save changes to the hard drive, execute

filetool.sh -bin a terminal window.

- Once you booted up from the disk, click on Apps and install

-

Install and Activate SSH

I used "How to install and configure OpenSSH (SSH Server) in Tiny Core Linux" as my guide for this work.- Click on Apps and install

- openssh.tcz

- Go to the ssh configuration files with

cd /usr/local/etc/ssh sudo cp sshd_config.example sshd_config- Using

vi, place the lineusr/local/etc/sshin the/opt/.xfiletool.lstfile. - Start the OpenSSH service via

sudo /usr/local/etc/init.d/openssh start - Using

vi, place the line/usr/local/etc/init.d/openssh startin the/opt/bootlocal.shfile. - Establish a password on the

tcaccount by using the commandpasswd. - Make the password permininate by putting the following lines in the

/opt/.xfiletool.lstfile.etc/passwdetc/shadowetc/group

- Test the installation by using ssh to login TCL from another system using

ssh tc@XT. - To permanently save changes to the hard drive, execute

filetool.sh -bin a terminal window.

- Click on Apps and install

-

Activate WiFi

Getting clear and up to date information on TCL WiFi isn't easy, but Easy Way: wicd and How to get wireless working proved to be the best sources.- Install the following extensions via TCL

Appsapplication (OnBoot):- usb-utils.tcz

- To download the latest USB device information by executing

sudo update-usbids.sh. - Now lets detect the type of WiFi USB adapter that is plugged into the Laptop. In my case, this WiFi adapter is detected via

lsusbas- USB ID =

0bda:8176 - Description =

Realtek Semiconductor RTL8188CUS 802.11n WLAN Adapter

- USB ID =

- The USB ID is listed as one of the Tiny Core Linux supported WiFi chips. Knowing this, we can install the suite of applications and firmware required to get the WiFi adapter operational. I install the following extensions via TCL

Appsapplication (OnBoot):- NOT SURE YOU NEED THIS: wifi.tcz

- firmware-rtlwifi.tcz

- wpa_supplicant.tcz

- wireless_tools.tcz

- Now pull the Ethernet connection and reboot (TCL seems to get confused when you try to operate with both Ethernet and WiFi connections).

- At this point you may verify the WiFi device with

iwconfig. You should see thatwlan0is operational. - Execute the program

sudo wpa_passphrase <YourSSID> <YourPassword> > /opt/wpa_supplicant.conf. This will place the network credentials in a file. - On the command line, execute the WPA2 utility8

sudo wpa_supplicant -Dwext -iwlan0 -c/opt/wpa_supplicant.conf -B. - On the command line, execute DHCP client program9

sudo udhcpc -iwlan0 -p/var/run/udcpc.wlan0.pid. - Now see if you can

pingfrom and to the laptop. - To permanently save changes to the hard drive, execute

filetool.sh -bin a terminal window. - As a final test, reboot and try out the WiFi.

- After a reboot, I found that WiFi wouldn't work (i.e.

iwconfigdidn't detect the WiFi adapter). I had to pull the WiFi adapter and reinstall it into the USB. I then executedsudo wpa_supplicant -Dwext -iwlan0 -c/opt/wpa_supplicant.conf -Bandsudo udhcpc -iwlan0 -p/var/run/udcpc.wlan0.pid.

- After a reboot, I found that WiFi wouldn't work (i.e.

- Install the following extensions via TCL

Tiny Core Linux Files

Once successfully installed, the Tiny Core Linux (TCL) files should be look like this:

The backup is controlled by two files /opt/.filetool.lst lists

everything to include,

and /opt/.xfiletool.lst lists everything to exclude.

Exclusions will override inclusions.

My /opt/.filetool.lst file looks like this

opt home usr/local/etc/ssh etc/passwd etc/shadow etc/group

My /opt/.xfiletool.lst file looks like this

Cache cache .cache XUL.mfasl XPC.mfasl mnt .adobe/Flash_Player/AssetCache .macromedia/Flash_Player .opera/opcache .opera/cache4 .Xauthority .wmx

bootsync.sh is the entry point for all items you need to run on boot,

while the boot waits for them to complete.

My /opt/bootsync.sh file looks like this

#!/bin/sh # put other system startup commands here, the boot process will wait until they complete. # Use bootlocal.sh for system startup commands that can run in the background # and therefore not slow down the boot process. /usr/bin/sethostname box /opt/bootlocal.sh &

bootlocal.sh is the entry point for all items that don’t need to be waited for.

This may include loading some non-essential module or starting some server.

My /opt/bootlocal.sh file looks like this

#!/bin/sh # put other system startup commands here /usr/local/sbin/basic-firewall noprompt /usr/local/etc/init.d/openssh start /usr/local/sbin/basic-firewall noprompt opt/alas etc/modprobe.conf usr/local/etc/asound.state

The program sudo wpa_passphrase <YourSSID> <YourPassword> was used to

created the network WPA2 WiFi credentials and placed in the file

/opt/wpa_supplicant.conf.

network={ ssid="74LL5" #psk="dfjgrigreiodjdeghry" psk=8477c7110cf5edex3e07aa82345fxefc4f2da4sd9x8fcc4ad3x83fef6d2416df }

The .xsession file sets up the default background,

starts any X-dependant programs you’ve configured,

and starts up the configured window manager.

My /home/tc/.xsession file looks like this

# This script will start a local X Window envirnment or use a remote Display Manager # Set to 1 if your wish to use remote Display Manager REMOTE=1 if [ $REMOTE == 1 ]; then Xvesa -query desktop -br -screen 1024x768x32 -shadow -3button -mouse /dev/input/mice,5 -I >/dev/null 2>&1 & export XPID=$! waitforX || ! echo failed in waitforX || exit "$DESKTOP" 2>/tmp/wm_errors & export WM_PID=$! [ -x $HOME/.setbackground ] && $HOME/.setbackground [ -x $HOME/.mouse_config ] && $HOME/.mouse_config & [ $(which "$ICONS".sh) ] && ${ICONS}.sh & [ -d "$HOME/.X.d" ] && find "$HOME/.X.d" -type f -print | while read F; do . "$F"; done else Xvesa -br -screen 1024x768x32 -shadow -3button -mouse /dev/input/mice,5 -nolisten tcp -I >/dev/null 2>&1 & export XPID=$! waitforX || ! echo failed in waitforX || exit "$DESKTOP" 2>/tmp/wm_errors & export WM_PID=$! [ -x $HOME/.setbackground ] && $HOME/.setbackground [ -x $HOME/.mouse_config ] && $HOME/.mouse_config & [ $(which "$ICONS".sh) ] && ${ICONS}.sh & [ -d "$HOME/.X.d" ] && find "$HOME/.X.d" -type f -print | while read F; do . "$F"; done fi

My /home/tc/.local/bin/localX.sh file looks like this

# This script will start a local X Window envirnment Xvesa -br -screen 1024x768x32 -shadow -3button -mouse /dev/input/mice,5 -nolisten tcp -I >/dev/null 2>&1 & export XPID=$! waitforX || ! echo failed in waitforX || exit "$DESKTOP" 2>/tmp/wm_errors & export WM_PID=$! [ -x $HOME/.setbackground ] && $HOME/.setbackground [ -x $HOME/.mouse_config ] && $HOME/.mouse_config & [ $(which "$ICONS".sh) ] && ${ICONS}.sh & [ -d "$HOME/.X.d" ] && find "$HOME/.X.d" -type f -print | while read F; do . "$F"; done

Tiny Core Linux Commands

To find the linux kernel version for the TCL your runing uname -or.

To check the running version of TCL, you can run the version command.

For example:

tc@XT:~$ uname -or 3.8.13-tinycore GNU/Linux tc@XT:~$ version 5.2

Once Installed, How Do You Manage the X Terminal

To kill the Xvesa X Server on TCL, press the Ctrl+Alt+Del key combination,

and you will get the TCL command line prompt.

To start the X Winodw System, do the following

# start the X Window System and brings up the Xvesa X Server using the remote Display Manager

. ./.xsession

Configuring Remote Computer (Ubuntu Desktop)

On the remote-computer (in my case, a Ubuntu desktop runing lightdm Display Manager),

you need to tell the Display Manager to accept logins from a remote X Server.

This is easily done by configuring the file /etc/lightdm/lightdm.conf so it contains

[SeatDefaults] user-session=ubuntu autologin-user=false xserver-allow-tcp=true greeter-session=unity-greeter [xdmcp] Enable=true

The key parameter to be added is xserver-allow-tcp.

There is no manpage for lighdm.conf, but there is an example that lists all the options

and a bit about what they do, just look in /usr/share/doc/lightdm/lightdm.conf.gz

For a more complete list of configuration parameters for lightDM Display Manager,

see the article "Disable guest session in Ubuntu 11.10" and

Understanding lightdm.conf.

Picking a New Window Manager for Remote Computer (Ubuntu Desktop)

Given my problems with Compiz stated earlier, I want to pick a simpler, lightweight Window Manger that could run on my ancient hardware. I researched my options with the aid of the articles "How-to: Picking a Window Manager in Linux" and "20 Most Nimble and Simple X Window Managers for Linux". I choose Fluxbox as my replacement Window Manger because of its simplicity and it widely praised. You Fluxbox Documentation will give most of what you need to configure this Window Manager. To install Fluxbox, and a companion tool for supporting desktop icons called fbdesk, use the following:

# install Fluxbox

sudo apt-get install fluxbox fbdesk

Xvesa X Server

Xvesa X Server is NOT a normal XFree86 X Server. It is part of the TinyX series of X Servers. Xvesa accepts all the standard options accepted by all X Servers, along with some specail options. They are part of the XFree86 package, but they are very different. They are designed for low memory use. It also turns out that they work better for some video chips than the normal XF86 xservers.

But one very important thing is they do NOT use the XF86Config file, like their bigger brothers.

Xvesa -query desktop -br -screen 1024x768x32 -shadow

- -nolisten trans-type disables a transport type. For example, TCP/IP connections can be disabled with -nolisten tcp. This option may be issued multiple times to disable listening to different transport types.

- -br sets the default root window to solid black instead of the standard root weave pattern.

- -shadow use a shadow framebuffer even if it is not strictly necessary. This may dramatically improve performance on some hardware.

- -I ignore all remaining arguments

To make this persistent, put tc/.xsession in the /opt/.filetool.lst.

-

Celeron is a brand name given by Intel Corp. to a number of different microprocessor models targeted at budget personal computers. Introduced in April 1998, the first Celeron branded CPU was based on the Pentium II branded core. Subsequent Celeron branded CPUs were based on the Pentium III, Pentium 4, Pentium M, and Intel Core branded processors. With Damn Small Linux loaded and running

cat /proc/cpuinfo, it shows the processor is of Intel CPU family 6 and model 11. This maps to Intel product code 80530, which makes it a Pentium III (codename Tualatin). ↩ -

Feature Description CPU 1066-MHz Intel Mobile Celeron processor Cache 128KB internal L2 cache, 32KB internal L1 cache Memory 128MB of 100MHz SDRAM standard (PC100), 512MB maximum system memory (two slots available only for memory modules)(144-pin/3.3V; 1.25-in slots) Mass Storage 10GB Enhanced-IDE hard drive, Built-in 3.5-inch 1.44-MB floppy disk drive, Built-in 24X maximum-speed CD-ROM drive Display 13.3-inch diagonal 1024 × 768 XGA TFT display with 16 million colors Video S3 Savage/1X graphics controller, 2X AGP graphics, 128-bit single-cycle 3D architecture video graphics controller, 8MB of embedded video SGRAM, external video resolutions/maximum colors/refresh rates: 800 × 600/16M colors/85Hz, 1024 × 768/16M colors/85Hz, 1280 × 1024/16M colors/85Hz, 1600 × 1200/64K colors/85Hz Audio 16-bit Sound Blaster Pro–compatible stereo sound (ESS Allegra), Stereo sound via headphone-out, microphone-in port, Polk Audio speakers, 3D-enhanced PCI bus audio, Supports CD-play while system is off, Built-in microphone Ports Two Universal Serial Bus (USB) ports, Serial port: 9-pin, 115,200 bps, Parallel port: 25-pin bi-directional ECP and EPP, 4-Mbps IrDA-compliant infrared port, PS/2 keyboard/mouse port, VGA: 15-pin, Composite TV-out, RJ-11 modem jack, RJ-45 jack, Headphone-out, microphone-in ports Communications Integrated 56Kbps, v.90-compatible, worldwide capable modem + 10/100 LAN combo Power Universal AC adapter: 100 to 240 Vac input; 19-Vdc, 3.16-A output, Built-in rechargeable 9-cell Lithium-Ion battery (with up to 4-hour run time) PC Card Slots One Type III or two Type II PC Card slots, CardBus-enabled (TI 1420) Weight 7.2lb with 13.3-in display Dimensions 13.03 × 10.76 × 1.59in Operating System Microsoft Windows 98, Second Edition -

Generally, a X Terminal, a predecessor to todays thin client, is a low-powered, diskless, quieter, and more reliable than desktop computers because they do not have any moving parts. I can't say this about this vintage laptop. ↩

-

Damn Small Linux also uses by default Busybox. BusyBox provides several stripped-down Unix tools in a single executable file. Its originally aim was to provide a complete bootable system on a single floppy that would serve both as a rescue disk and as an installer for the Debian distribution. Busybox's use now is more focused on embedded operating systems with very limited resources. ↩

-

XDMCP is inherently insecure as it does not encrypt your traffic. Therefore, only use XDMCP on a wired network that you you trust or a solidly secure wireless network. Also, consider using alternatives that feature security (and often compression) such as FreeNX. XDMCP also uses a large amount of bandwidth because it uses no compression. A 100Mb network may be necessary. However, the lack of compression can make XDMCP provide very fast graphics when the bandwidth is available. ↩

-

An alternative is to use the graphics configuration editor

dconf-editor. ↩ -

There appears to be some efforts to create a secure solution using a tool call S-Terminal, but since this would need to be supported on Tiny Core Linux (which it is not), this will not help me. ↩

-

wpa_supplicantis a free software implementation of an IEEE 802.11i supplicant for Linux. Included with the supplicant are a GUI and a command-line utility for interacting with the running supplicant. From either of these interfaces it is possible to review a list of currently visible networks, select one of them, provide any additional security information needed to authenticate with the network (for example, a passphrase, or username and password). ↩ -

Udhcpc is a very small DHCP client program geared towards embedded systems. The letters are an abbreviation for Micro - DHCP - Client (µDHCPc). The program tries to be fully functional and RFC 2131 compliant. ↩