Using Secure Shell (SSH) with

public key authentication is more secure than just using password authentication.

This is particularly important if the computer is visible on the internet.

Using SSH, along with a few other tricks,

will drastically improve the security of your computer.

Using Secure Shell (SSH) with

public key authentication is more secure than just using password authentication.

This is particularly important if the computer is visible on the internet.

Using SSH, along with a few other tricks,

will drastically improve the security of your computer.

In conventional password authentication you prove you are who you claim to be by proving that you know the correct password. (Password authentication and file encryption use a different methodology for authentication than you would use to secure a website.) The only way to prove you know the password is to tell the server what you think the password is. This means that if the server has been hacked, or spoofed, an attacker can learn your password.

Public key authentication solves this problem. You generate a key pair, consisting of a public key (which everybody is allowed to know) and a private key (which you keep secret and do not give to anybody). The private key is able to generate signatures. A signature created using your private key cannot be forged by anybody who does not have that key; but anybody who has your public key can verify that a particular signature is genuine.

Each key is a large number with special mathematical properties.

The private key is kept on the computer you log in from,

while the public key is stored on the .ssh/authorized_keys

file on all the computers you want to log in to.

When you log in to a computer,

the SSH server uses the public key to "lock" messages in a way that can only be

"unlocked" by your private key.

This means that even the most resourceful attacker can't snoop on,

or interfere with, your session.

As an extra security measure,

most SSH programs store the private key in a passphrase-protected format,

so that if your computer is stolen or broken in to,

you should have enough time to disable your old public key

before they break the passphrase and start using your key.

Public key authentication is a much better solution than passwords for most people. In fact, if you don't mind leaving a private key unprotected on your hard disk, you can even use keys to do secure automatic log-ins - as part of a network backup, for example.

The general process of creating a passwordless login is as follows (see "How To Set Up SSH Keys on Ubuntu 16.04":

- Create a public/private key pair on the local machine with

ssh-keygen. - Run

ssh-agentto cache login credentials for the session.ssh-agentrequires the user to "unlock" the private key first. - Put the public key on any remote machines with

ssh-copy-id. - Login to the remote machine without entering the password

Step 1: Start on the Local Machine

To establish your SSH based authentication, your start on the local machine, that is, the system from which you log into the remote machine. It is from the local machine that you will establish the SSH keys and push the public key to the remote machine.

Secure Shell (SSH) needs to already be installed and configured.

To install, just do sudo apt-get install openssh-server

and follow the procedures here to configure.

Step 2: Checking for Existing SSH Keys

Before you generate an SSH key, you should check to see if you have any existing SSH keys. To do this, open terminal and enter:

# Lists the files in your .ssh directory

ls -al ~/.ssh

By default, the filenames of the keys are

~/.ssh/id_rsa for your private key and ~/.ssh/id_rsa.pub for your public key.

If you don't have an existing public and private key pair, or don't wish to use any that are available, then generate a new SSH key.

If you see an existing public and private key pair listed

(for example id_rsa.pub and id_rsa)

that you would like to use to connect to your remote machine,

you can add your SSH key to the ssh-agent.

Step 3: Generating a New SSH Key

After you've checked for existing SSH keys,

you can generate a new SSH key to use for authentication,

then add it to the ssh-agent.

When you're prompted to "Enter a file in which to save the key," press Enter.

This accepts the default file location.

At the next prompt, type a secure passphrase.

In a terminal, do the following:

# Creates a new ssh key, using the provided email as a label $ ssh-keygen -t rsa -b 4096 -C "[email protected]" Generating public/private rsa key pair. Enter file in which to save the key (/home/jeff/.ssh/id_rsa): /home/jeff/.ssh/id_rsa already exists. Overwrite (y/n)? y Enter passphrase (empty for no passphrase): Enter same passphrase again: Your identification has been saved in /home/jeff/.ssh/id_rsa. Your public key has been saved in /home/jeff/.ssh/id_rsa.pub. The key fingerprint is: 2b:69:c2:53:9a:2d:a7:68:b7:88:e4:ba:35:e3:f5:3c [email protected] The key's randomart image is: +--[ RSA 4096]----+ | ... | | . | |.o.e. C | |= oO. e . | |.oB.3 = S E | |. * + + . | |. . 3 o 4 | | o | |. 2 | +-----------------+

The randomart is meant to be an easier way for humans to visually validate keys, a "visual fingerprint" of your key. You do not need to save these. The key fingerprint is used by your local machine for easy identification/verification of the host you are connecting to. If the fingerprint changes, the machine you are connecting to has changed their public key.

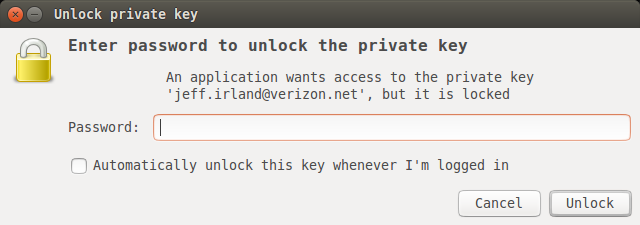

The passphrase provides a securing method for your SSH keys and configuring an authentication agent so that you won't have to re-enter your passphrase every time you use your keys. On Ubuntu, you'll need to enter only once after you have logged in. You'll be prompted with a screen like this:

Step 3B: Changing Your Passphrase

Sooner or later you'll want to change the passphrase on your private key.

You can change the passphrase for an existing private keys without regenerating the key pair.

Just type the command ssh-keygen -p.

See an example below:

# change the passphrase for an existing private key $ ssh-keygen -p Enter file in which the key is (/home/jeff/.ssh/id_rsa): Enter old passphrase: Key has comment '/home/jeff/.ssh/id_rsa' Enter new passphrase (empty for no passphrase): Enter same passphrase again: Your identification has been saved with the new passphrase.

Step 3C: Retrieve Your Public Key from Your Private Key

The following command will retrieve the public key from a private key:

generate your public key from your private key ssh-keygen -y

This can be useful, for example, if your server provider generated your SSH key for you and you were only able to download the private key portion of the key pair.

NOTE: You cannot retrieve the private key if you only have the public key.

Step 4: Adding your SSH Key to the ssh-agent

The ssh-agent is responsible for manging you multiple keys.

You enter the passphrase once, and after that,

ssh-agent keeps your key in its memory and pulls it up whenever it is asked for it.

It will be available for the duration of your terminal session,

allowing you to connect in the future without re-entering the passphrase.

The idea is that ssh-agent is started in the beginning of an X-session or a login session,

and all other windows or programs are started as clients to the ssh-agent program.

To ensure ssh-agent is enabled:

# start the ssh-agent in the background eval "$(ssh-agent -s)" Agent pid 59566

Add your SSH key to the ssh-agent:

ssh-add ~/.ssh/id_rsa

You can have a look at your currently loaded keys by using ssh-add -l.

This is also important if you need to forward your SSH credentials (shown below).

Step 5: Copy Public Key to Remote Machine

Now you must provide the public keys to your remote machine.

The easiest way to copy your public key is to use a utility called ssh-copy-id.

For this method to work,

you must already have password-based SSH working on the remote machine.

Simply do this ssh-copy-id user_name@remote_machine.

In my example:

# copy public keys to your remote machine $ ssh-copy-id pi@mesh01 The authenticity of host 'mesh01 (192.168.1.179)' can't be established. ECDSA key fingerprint is e6:49:7d:c3:48:e3:21:72:b3:2e:12:2a:d8:bc:13:15. Are you sure you want to continue connecting (yes/no)? yes /usr/bin/ssh-copy-id: INFO: attempting to log in with the new key(s), to filter out any that are already installed /usr/bin/ssh-copy-id: INFO: 2 key(s) remain to be installed -- if you are prompted now it is to install the new keys pi@mesh01's password: Number of key(s) added: 2 Now try logging into the machine, with: "ssh 'pi@mesh01'" and check to make sure that only the key(s) you wanted were added.

This procedure has created the file .ssh/authorized_keys under the home directory

of the remote system.

Your d_rsa.pub file has been copied into .ssh/authorized_keys.

If you do not have password-based SSH access to your server available, you will have to do the above process manually.

NOTE: The

ssh-copy-idcreates the.sshdirectory and.ssh/authorized_keysfile with the correct permissions. However, if you've created them manually and need to fix permissions. You can run the following commands to do this:chmod 700 ~/.sshandchmod 600 ~/.ssh/authorized_keys.

Step 5B: Granting Access to Multiple Keys

The .ssh/authorized_keys file you created above uses a very simple format:

it can contain many keys as long as you put one key on each line in the file.

If you have multiple keys (for example, one on each of your laptops)

or multiple developers you need to grant access to,

just follow the same instructions above using ssh-copy-id

or manually editing the file to paste in additional keys, one on each line.

When you're done, the .ssh/authorized_keys file will look something like this:

ssh-rsa AAAAB3NzaC1yc2EAAAADAQABAAABAQDSkT3A1j89RT/540ghIMHXIVwNlAEM3WtmqVG7YN/wYwtsJ8iCszg4/lXQsfLFxYmEVe8L9atgtMGCi5QdYPl4X/c+5YxFfm88Yjfx+2xEgUdOr864eaI22yaNMQ0AlyilmK+PcSyxKP4dzkf6B5Nsw8lhfB5n9F5md6GHLLjOGuBbHYlesKJKnt2cMzzS90BdRk73qW6wJ+MCUWo+cyBFZVGOzrjJGEcHewOCbVs+IJWBFSi6w1enbKGc+RY9KrnzeDKWWqzYnNofiHGVFAuMxrmZOasqlTIKiC2UK3RmLxZicWiQmPnpnjJRo7pL0oYM9r/sIWzD6i2S9szDy6aZ mike@laptop1 ssh-rsa AAAAB3NzaC1yc2EAAAADAQABAAABAQCzlL9Wo8ywEFXSvMJ8FYmxP6HHHMDTyYAWwM3AOtsc96DcYVQIJ5VsydZf5/4NWuq55MqnzdnGB2IfjQvOrW4JEn0cI5UFTvAG4PkfYZb00Hbvwho8JsSAwChvWU6IuhgiiUBofKSMMifKg+pEJ0dLjks2GUcfxeBwbNnAgxsBvY6BCXRfezIddPlqyfWfnftqnafIFvuiRFB1DeeBr24kik/550MaieQpJ848+MgIeVCjko4NPPLssJ/1jhGEHOTlGJpWKGDqQK+QBaOQZh7JB7ehTK+pwIFHbUaeAkr66iVYJuC05iA7ot9FZX8XGkxgmhlnaFHNf0l8ynosanqt henry@laptop2

Step 6: Logging on the Remote Machine

If you have successfully completed one of the procedures above, you should be able to log into the remote machine without the remote account's password. The login process is the same:

# login password-less

ssh user_name@remote_machine

Step 7: Disabling Password Authentication on Remote Machine

If you were able to login to your remote machine using SSH without a password, you have successfully configured SSH key-based authentication to your remote account. However, your password-based authentication mechanism is still active, meaning that your server is still exposed to brute-force attacks.

Before proceeding,

make sure that you either have SSH key-based authentication configured

for the root account on this server, or preferably,

that you have SSH key-based authentication configured for an account

on this server with sudo access.

This step will lock down password-based logins,

so ensuring that you have will still be able to get administrative access is essential.

Login into the remote machine,

either as root or with an account with sudo privileges.

Open the SSH daemon's configuration file: /etc/ssh/sshd_config.

Inside the file, search for a directive called PasswordAuthentication.

This may be commented out.

Uncomment the line and set the value to "no".

This will disable your ability to log in through SSH using account passwords.

Save and close the file and you are finished.

To actually implement the changes we just made,

you must restart the SSH service.

On Ubuntu or Debian machines, you can issue this command: sudo service ssh restart.

After completing this step, all accounts on the remote machine will only allow login using SSH keys.

Step 8: Disabling SSH Login as Root on Remote Machine

For security purposes, you may want to not allow anyone to log into

the remote machine as root over SSH.

You still want the root account to exist,

just do not want it to be able to be logged into remotely.

You can use sudo to gain root privileges anytime you need them.

You can do this by putting the following line into /etc/ssh/sshd_config:

# deny ssh users root logins

PermitRootLogin no

Step 9: Protecting SSH with Fail2Ban

Any server that is exposed to the Internet is susceptible to attacks from malicious parties (read this if you need convincing). If your system requires authentication, illegitimate users and bots will attempt to break into your system by repeatedly trying to authenticate using different credentials (aka brute-force attacks).

By default, fail2ban will take action when three authentication failures have been detected in 10 minutes, and the default ban time is for 10 minutes. The default for number of authentication failures necessary to trigger a ban is overridden in the SSH portion of the default configuration file to allow for 6 failures before the ban takes place. All of this is entirely configurable by the root user.

SSH is particularly a focus of such attacks. The utility fail2ban was created to help mitigate these attacks. Fail2ban monitors the logs of common services to spot patterns in authentication failures, and then alters the firewall rules to ban addresses that have unsuccessfully attempted to log in a certain number of times.

A good article to understand how fail2ban works is "How Fail2Ban Works to Protect Services on a Linux Server". To get fail2ban up and running, check out the article "HowTo: Install and Configure Fail2Ban".

Trouble Shooting

There are many things that can stop SSH from working. Generally problems with SSH connections fall into two groups - network related and server related. Here are some good references: